Abstract

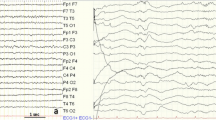

Typical absences are brief (seconds) generalised seizures of sudden onset and termination. They have 2 essential components: clinically, the impairment of consciousness (absence) and, generalised 3 to 4Hz spike/polyspike and slow wave discharges on electroencephalogram (EEG). They differ fundamentally from other seizures and are pharmacologically unique. Their clinical and EEG manifestations are syndrome-related. Impairment of consciousness may be severe, moderate, mild or inconspicuous. This is often associated with motor manifestations, automatisms and autonomic disturbances. Clonic, tonic and atonic components alone or in combination are motor symptoms; myoclonia, mainly of facial muscles, is the most common. The ictal EEG discharge may be consistently brief (2 to 5 seconds) or long (15 to 30 seconds), continuous or fragmented, with single or multiple spikes associated with the slow wave. The intradischarge frequency may be constant or may vary (2.5 to 5Hz).

Typical absences are easily precipitated by hyperventilation in about 90% of untreated patients. They are usually spontaneous, but can be triggered by photic, pattern, video games stimuli, and mental or emotional factors.

Typical absences usually start in childhood or adolescence. They occur in around 10 to 15% of adults with epilepsies, often combined with other generalised seizures. They may remit with age or be lifelong.

Syndromic diagnosis is important for treatment strategies and prognosis. Absences may be severe and the only seizure type, as in childhood absence epilepsy. They may predominate in other syndromes or be mild and nonpredominant in syndromes such as juvenile myoclonic epilepsy where myoclonic jerks and generalised tonic clonic seizures are the main concern. Typical absence status epilepticus occurs in about 30% of patients and is more common in certain syndromes, e.g. idiopathic generalised epilepsy with perioral myoclonia or phantom absences.

Typical absence seizures are often easy to diagnose and treat. Valproic acid, ethosuximide and lamotrigine, alone or in combination, are first-line therapy. Valproic acid controls absences in 75% of patients and also GTCS (70%) and myoclonic jerks (75%); however, it may be undesirable for some women. Similarly, lamotrigine may control absences and GTCS in possibly 50 to 60% of patients, but may worsen myoclonic jerks; skin rashes are common. Ethosuximide controls 70% of absences, but it is unsuitable as monotherapy if other generalised seizures coexist. A combination of any of these 3 drugs may be needed for resistant cases. Low dosages of lamotrigine added to valproic acid may have a dramatic beneficial effect. Clonazepam, particularly in absences with myoclonic components, and acetazolamide may be useful adjunctive drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Commission of Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1981; 22: 489–501

Panayiotopoulos CP, Obeid T, Waheed G. Differentiation of typical absence seizures in epileptic syndromes: a video EEG study of 224 seizures in 20 patients. Brain 1989; 112: 1039–56

Panayiotopoulos CP. Absence epilepsies. In: Engel JJ, Pedley TA, editors. Epilepsy: a comprehensive textbook. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott-Raven, 1997: 2327–46

Panayiotopoulos CP. Typical absence seizures. In: Gilman S, editor. Neurobase. San Diego (CA): Arbor Publishing Corp, 2000

Marescaux C, Vergnes M. Animal models of absence seizures and absence epilepsies. In: Duncan JS, Panayiotopoulos CP, editors. Typical absences and related epileptic syndromes. London: Churchill Comunications Europe, 1995: 8–18

Danober L, Deransart C, Depaulis A, et al. Pathophysiological mechanisms of genetic absence epilepsy in the rat. Prog Neurobiol 1998; 55: 27–57

Futatsugi Y, Riviello Jr JJ. Mechanisms of generalized absence epilepsy. Brain Dev 1998; 20: 75–9

Hosford DA, Caddick SJ, Lin FH. Generalized epilepsies: emerging insights into cellular and genetic mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurol 1997; 10: 115–20

Panayiotopoulos CP. Typical absence seizures and their treatment. Arch Dis Child 1999; 81: 351–5

Parker AP, Agathonikou A, Robinson RO, et al. Inappropriate use of carbamazepine and vigabatrin in typical absence seizures. Dev Med Child Neurol 1998; 40: 517–9

Panayiotopoulos CP. Importance of specifying the type of epilepsy. Lancet 1999; 354: 2002–3

Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia 1989; 30: 389–99

Loiseau P, Duche B, Pedespan JM. Absence epilepsies. Epilepsia 1995; 36: 1182–6

Hirsch E, Marescaux C. What are the relevant criteria for a better classification of epileptic syndromes with typical absences? In: Malafosse A, Genton P, Hirsch E, et al., editors. Idiopathic generalised epilepsies. London: John Libbey & Company Ltd, 1994: 87–93

Loiseau P. Childhood absence epilepsy. In: Roger J, Bureau M, Dravet C, et al., editors. Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood and adolescence. London: John Libbey & Company, 1992: 135–50

Bouma PA, Westendorp RG, van Dijk JG, et al. The outcome of absence epilepsy: a meta-analysis. Neurology 1996; 47: 802–8

Bartolomei F, Roger J, Bureau M, et al. Prognostic factors for childhood and juvenile absence epilepsies. Eur Neurol 1997; 37: 169–75

Tassinari CA, Bureau M, Thomas P. Epilepsy with myoclonic absences. In: Roger J, Bureau M, Dravet C, et al., editors. Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood and adolescence. London: John Libbey & Company, 1992: 151–60

Tassinari CA, Michelucci R, Rubboli G, et al. Myoclonic absence epilepsy. In: Duncan JS, Panayiotopoulos CP, editors. Typical absences and related epileptic syndromes. London: Churchill Communications Europe, 1995: 187–95

Janz D, Christian W. Impulsiv-Petit mal. Zeitschrift f Nervenheilkunde 1957; 176: 346–86

Panayiotopoulos CP, Obeid T, Tahan AR. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: a 5-year prospective study. Epilepsia 1994; 35: 285–96

Delgado-Escueta AV, Medina MT, Serratosa JM, et al. Mapping and positional cloning of common idiopathic generalized epilepsies: juvenile myoclonus epilepsy and childhood absence epilepsy. Adv Neurol 1999; 79: 351–74

Panayiotopoulos CP, Obeid T, Waheed G. Absences in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: a clinical and video-electroencephalographic study. Ann Neurol 1989; 25: 391–7

Grunewald RA, Panayiotopoulos CP. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: a review. Arch Neurol 1993; 50: 594–8

Duncan JS, Panayiotopoulos CP. Eyelid myoclonia with absences. London: John Libbey & Company Ltd, 1996

Giannakodimos S, Panayiotopoulos CP. Eyelid myoclonia with absences in adults: a clinical and video-EEG study. Epilepsia 1996; 37: 36–44

Panayiotopoulos CP. Eyelid myoclonia with or without absences. In: Gilman S, editor. Neurobase. San Diego (CA): Arbor Publishing Corp, 2000

Clemens B. Perioral myoclonia with absences: a case report with EEG and voltage mapping analysis. Brain Dev 1997; 19: 353–8

Panayiotopoulos CP, Ferrie CD, Giannakodimos S, et al. Perioral myoclonia with absences: a new syndrome. In: Wolf P, editor. Epileptic seizures and syndromes. London: John Libbey & Company Ltd, 1994: 143–53

Agathonikou A, Panayiotopoulos CP, Giannakodimos S, et al. Typical absence status in adults: diagnostic and syndromic considerations. Epilepsia 1998; 39: 1265–76

Doose H, Volzke E, Scheffner D. Verlaufsformen kindlicher epilepsien mit spike wave-absencen. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 1965; 207: 394–415

Doose H. Absence epilepsy of early childhood:genetic aspects. Eur J Pediatr 1994; 153: 372–7

Doose H. Absence epilepsy of early childhood. In: Wolf P, editor. Epileptic seizures and syndromes. London: John Libbey & Company Ltd, 1994: 133–5

Panayiotopoulos CP, Koutroumanidis M, Giannakodimos S, et al. Idiopathic generalised epilepsy in adults manifested by phantom absences, generalised tonic-clonic seizures, and frequent absence status. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 1997; 63: 622–7

Wilkins A. Towards an understanding of reflex epilepsy and absence. In: Duncan JS, Panayiotopoulos CP, editors. Typical absences and related epileptic syndromes. London: Churchill Communications Europe, 1995: 196–205

Duncan JS, Panayiotopoulos CP. Typical absences with specific modes of precipitation (reflex absences): clinical aspects. In: Duncan JS, Panayiotopoulos CP, editors. Typical absences and related epileptic syndromes. London: Churchill Communications Europe, 1995: 206–12

Agathonikou A, Giannakodimos S, Koutroumanidis M, et al. Idiopathic generalised epilepsies in adults with onset of typical absences before the age of 10 years [abstract]. Epilepsia 1997; 38Suppl. 3:213

Ferrie CD, Giannakodimos S, Robinson RO, et al. Symptomatic typical absence seizures. In: Duncan JS, Panayiotopoulos CP, editors. Typical absences and related epileptic syndromes. London: Churchill Communications Europe, 1995: 241–52

Raymond AA, Fish DR, Stevens JM, et al. Subependymal heterotopia: a distinct neuronal migration disorder associated with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994; 57: 1195–202

Sander JWAS. The epidemiology and prognosis of typical absence seizures. In: Duncan JS, Panayiotopoulos CP, editors. Typical absences and related epileptic syndromes. London: Churchill Communications Europe, 1995: 135–44

Panayiotopoulos CP. Benign childhood partial seizures and related epileptic syndromes. London: John Libbey & Company Ltd, 1999

Loiseau J, Loiseau P, Guyot M, et al. Survey of seizure disorders in the French southwest I. Incidence of epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia 1990; 31: 391–6

Olsson I. Epidemiology of absence epilepsy I: concept and incidence. Acta Paediatr Scand 1988; 77: 860–6

Blom S, Heijbel J, Bergfors PG. Incidence of epilepsy in children: a follow-up study three years after the first seizure. Epilepsia 1978; 19: 343–50

Callenbach PM, Geerts AT, Arts WF, et al. Familial occurrence of epilepsy in children with newly diagnosed multiple seizures: dutch study of epilepsy in childhood. Epilepsia 1998; 39: 331–6

Berg AT, Levy SR, Testa FM, et al. Classification of childhood epilepsy syndromes in newly diagnosed epilepsy: interrater agreement and reasons for disagreement. Epilepsia 1999; 40: 439–44

Hosford DA, Wang Y. Utility of the lethargic (lh/lh) mouse model of absence seizures in predicting the effects of lamotrigine, vigabatrin, tiagabine, gabapentin, and topiramate against human absence seizures. Epilepsia 1997; 38: 408–14

Coulter DA. Antiepileptic drug cellular mechanisms of action: where does lamotrigine fit in? J Child Neurol 1997; 12Suppl. 1:S2–9

Coulter DA, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Characterization of ethosuximide reduction of low-threshold calcium current in thalamic neurons. Ann Neurol 1989; 25: 582–93

Hosford DA, Lin FH, Wang Y, et al. Studies of the lethargic (lh/lh) mouse model of absence seizures: regulatory mechanisms and identification of the lh gene. Adv Neurol 1999; 79: 239–52

Hosford DA, Lin F, Cao Z, et al. Action of anti-epileptic drugs in animal models: mechanistic frame-work of absence seizures with a focus on the lethargic (lh/lh) mouse model. In: Duncan JS, Panayiotopoulos CP, editors. Typical absences and related epileptic syndromes. London: Churchill Communications Europe, 1995: 41–50

Gibbs JW, Schroder GB, Coulter DA. GABAA receptor function in developing rat thalamic reticular neurons: whole cell recordings of GABA-mediated currents and modulation by clonazepam. J Neurophysiol 1996; 76: 2568–79

Liu Z, Vergnes M, Depaulis A, et al. Evidence for a critical role of GABAergic transmission within the thalamus in the genesis and control of absence seizures in the rat. Brain Res 1991; 545: 1–7

Ryvlin P, Mauguiere F. Functional imaging in idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1998; 154: 691–3

Duncan JS. Positron emission tomography receptor studies. Adv Neurol 1999; 79: 893–9

Woermann FG, Free SL, Koepp MJ, et al. Abnormal cerebral structure in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy demonstrated with voxel-based analysis of MRI. Brain 1999; 122 (Pt 11): 2101–8

Woermann FG, Sisodiya SM, Free SL, et al. Quantitative MRI in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Evidence of widespread cerebral structural changes. Brain 1998; 121 (Pt 9): 1661–7

Meencke HJ, Janz D. The significance of microdysgenesia in primary generalized epilepsy: an answer to the considerations of Lyon and Gastaut. Epilepsia 1985; 26: 368–71

Lennox WG, Lennox MA. Epilepsy and related disorders. Boston (MA): Little, Brown & Co., 1960

Berkovic SF, Howell RA, Hay DA, et al. Epilepsies in twins: genetics of the major epilepsy syndromes. Ann Neurol 1998; 43: 435–45

Bianchi A, Italian LAE Collaborative Group. Study of concordance of symptoms in families with absence epilepsies. In: Duncan JS, Panayiotopoulos CP, editors. Typical absences and related epileptic syndromes. London: Churchill Communications Europe, 1995: 328–37

Berkovic SF, Howell RA, Hay DA, et al. Epilepsies in twins. In: Wolf P, editor. Epileptic seizures and syndromes. London: John Libbey & Company Ltd, 1994: 157–64

Serratosa JM, Delgado-Escueta AV, Medina MT, et al. Clinical and genetic analysis of a large pedigree with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Ann Neurol 1996; 39: 187–95

Elmslie FV, Rees M, Williamson MP, et al. Genetic mapping of a major susceptibility locus for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy on chromosome 15q. Hum Mol Genet 1997; 6: 1329–34

Bate L, Gardiner RM. Genetics of inherited epilepsies. Epileptic Disord 1999; 1:7–19

Greenberg DA, Durner M, Keddache M, et al. Reproducibility and complications in gene searches: linkage on chromosome 6, heterogeneity, association, and maternal inheritance in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 66: 508–16

Durner M, Shinnar S, Resor SR, et al. No evidence for a major susceptibility locus for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy on chromosome 15q. Am J Med Genet 2000; 96: 49–52

Durner M, Zhou G, Fu D, et al. Evidence for linkage of adolescent-onset idiopathic generalized epilepsies to chromosome 8-and genetic heterogeneity. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 64: 1411–9

Fong GC, Shah PU, Gee MN, et al. Childhood absence epilepsy with tonic-clonic seizures and electroencephalogram 3–4Hz spike and multispike-slow wave complexes: linkage to chromosome 8q24. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 63: 1117–29

Noebels JL. Genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of inherited spike- and -wave epilepsies. In: Malafosse A, Genton P, Hirsch E, et al., editors. Idiopathic generalized epilepsies: clinical, experimental and genetic aspects. London: John Libbey & Company, 1994: 215–25

Wirrell EC, Camfield PR, Gordon KE, et al. Will a critical level of hyperventilation-induced hypocapnia always induce an absence seizure? Epilepsia 1996; 37: 459–62

Panayiotopoulos CP, Chroni E, Daskalopoulos C, et al. Typical absence seizures in adults: clinical, EEG, video-EEG findings and diagnostic/syndromic considerations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 1992; 55: 1002–8

Panayiotopoulos CP. Lamictal (lamotrigine) monotherapy for typical absence seizures in children. Epilepsia 2000; 41: 357–9

Lombroso CT. Consistent EEG focalities detected in subjects with primary generalized epilepsies monitored for two decades. Epilepsia 1997; 38: 797–812

Wirrell EC, Camfield CS, Camfield PR, et al. Long-term prognosis of typical childhood absence epilepsy: remission or progression to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Neurology 1996; 47: 912–8

Obeid T. Clinical and genetic aspects of juvenile absence epilepsy. J Neurol 1994; 241: 487–91

Epilim. Product monograph. Surrey: Sanofi Winthrop Ltd, 1995

Richens A. Ethosuximide and valproate. In: Duncan JS, Panayiotopoulos CP, editors. Typical absences and related epileptic syndromes. London: Churchill Comunications Europe, 1995: 361–7

Erenberg G, Rothner AD, Henry CE, et al. Valproic acid in the treatment of intractable absence seizures in children: a single-blind clinical and quantitative EEG study. Am J Dis Child 1982; 136: 526–9

Villarreal HJ, Wilder BJ, Willmore LJ, et al. Effect of valproic acid on spike and wave discharges in patients with absence seizures. Neurology 1978; 28: 886–91

Berkovic SF, Andermann F, Guberman A, et al. Valproate prevents the recurrence of absence status. Neurology 1989; 39: 1294–7

Davis R, Peters DH, McTavish D. Valproic acid: a reappraisal of its pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy in epilepsy. Drugs 1994; 47: 332–72

Jeavons PM, Clark JE, Maheshwari MC. Treatment of generalized epilepsies of childhood and adolescence with sodium valproate (‘epilim’). Dev Med Child Neurol 1977; 19: 9–25

Covanis A, Gupta AK, Jeavons PM. Sodium valproate: monotherapy and polytherapy. Epilepsia 1982; 23: 693–720

Johannessen CU. Mechanisms of action of valproate: a commentatory. Neurochem Int 2000; 37: 103–10

Macdonald RL, Kelly KM. Antiepileptic drug mechanisms of action. Epilepsia 1995; 36Suppl. 2: S2–12

Loscher W. Valproate: a reappraisal of its pharmacodynamic properties and mechanisms of action. Prog Neurobiol 1999; 58: 31–59

Chappell KA, Markowitz JS, Jackson CW. Is valproate pharmacotherapy associated with polycystic ovaries? Ann Pharmacother 1999; 33: 1211–6

Acharya S, Bussel JB. Hematologic toxicity of sodium valproate. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2000; 22: 62–5

Bryant AE, Dreifuss FE. Valproic acid hepatic fatalities III: US experience since 1986. Neurology 1996; 46: 465–9

Delgado-Escueta AV, Janz D. Consensus guidelines: preconception counseling, management, and care of the pregnant woman with epilepsy. Neurology 1992; 42: 149–60

Laegreid L, Kyllerman M, Hedner T, et al. Benzodiazepine amplification of valproate teratogenic effects in children of mothers with absence epilepsy. Neuropediatrics 1993; 24:88–92

Isojarvi JI, Rattya J, Myllyla W, et al. Valproate, lamotrigine, and insulin-mediated risks in women with epilepsy. Ann Neurol 1998; 43: 446–51

Genton P, Bauer J, Duncan S, et al. On the association between valproate and polycystic ovary syndrome. Epilepsia 2001; 42: 295–304

Isojarvi JI, Tauboll E, Tapanainen JS, et al. On the association between valproate and polycystic ovary syndrome: a response and an alternative view. Epilepsia 2001; 42: 305–10

Herzog AG, Schachter SC. Valproate and polycystic ovarian syndrome: final thoughts. Epilepsia 2001; 42: 311–5

Yuen AW, Land G, Weatherley BC, et al. Sodium valproate acutely inhibits lamotrigine metabolism. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1992; 33: 511–3

Faught E, Morris G, Jacobson M, et al. Adding lamotrigine to valproate: incidence of rash and other adverse effects. Postmarketing Antiepileptic Drag Survey (PADS) Group. Epilepsia 1999; 40: 1135–40

Mattson RH, Cramer JA. Valproic acid and ethosuximide interaction. Ann Neurol 1980; 7: 583–4

Oguni H, Uehara T, Tanaka T, et al. Dramatic effect of ethosuximide on epileptic negative myoclonus: implications for the neurophysiological mechanism. Neuropediatrics 1998; 29: 29–34

Snead OC, Hosey LC. Treatment of epileptic falling spells with ethosuximide. Brain Dev 1987; 9: 602–4

Wallace SJ. Myoclonus and epilepsy in childhood: a review of treatment with valproate, ethosuximide, lamotrigine and zonisamide. Epilepsy Res 1998; 29: 147–54

Penry JK, Porter RJ, Dreifuss FE. Ethosuximide: relation of plasma levels to clinical control. In: Woodbury DM, Penry JK, Schmidt RP, editors. Antiepileptic drugs. New York (NY): Raven Press, 1972: 431–41

Sherwin AL, Robb JP. Ethosuximide: relation of plasma levels to clinical control. In: Woodbury DM, Penry JK, Schmidt RP, editors. Antiepileptic drugs. New York (NY): Raven Press 1972:443–8

Browne TR, Dreifuss FE, Dyken PR, et al. Ethosuximide in the treatment of absence (peptit mal) seizures. Neurology 1975; 25: 515–24

Blomquist HK, Zetterlund B. Evaluation of treatment in typical absence seizures. The roles of long-term EEG monitoring and ethosuximide. Acta Paediatr Scand 1985; 74: 409–15

Callaghan N, O’Hare J, O’Driscoll D, et al. Comparative study of ethosuximide and sodium valproate in the treatment of typical absence seizures (petit mal). Dev Med Child Neurol 1982; 24: 830–6

Sato S, White BG, Penry JK, et al. Valproic acid versus ethosuximide in the treatment of absence seizures. Neurology 1982; 32: 157–63

Martinovic Z. Comparison of ethosuximide with sodium valproate. In: Parsonage M, Grant RHE, Craig AG, et al., editors. Advances in epileptology. XIV Epilepsy International Symposium. New York (NY): Raven Press, 1983: 301–5

Lytton WW, Sejnowski TJ. Computer model of ethosuximide’s effect on a thalamic neuron. Ann Neurol 1992; 32: 131–9

Panayiotopoulos CP, Ferrie CD, Knott C, et al. Interaction of lamotrigine with sodium valproate [letter]. Lancet 1993; 341: 445

Barron TF, Hunt SL, Hoban TF, et al. Lamotrigine monotherapy in children. Pediatr Neurol 2000; 23: 160–3

Culy CR, Goa KL. Lamotrigine: a review of its use in childhood epilepsy. Paediatr Drugs 2000; 2: 299–330

Gericke CA, Picard F, Saint-Martin A, et al. Efficacy of lamotrigine in idiopathic generalized epilepsy syndromes: a video-EEG-controlled, open study. Epileptic Disord 1999; 1: 159–65

Ferrie CD, Robinson RO, Knott C, et al. Lamotrigine as an add-on drug in typical absence seizures. Acta Neurol Scand 1995; 91: 200–2

Buchanan N. Lamotrigine in the treatment of absence seizures [letter]. Acta Neurol Scand 1995; 92: 348

Buchanan N. The use of lamotrigine in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Seizure 1996; 5: 149–51

Buoni S, Grosso S, Fois A. Lamotrigine in typical absence epilepsy. Brain Dev 1999; 21: 303–6

Frank LM, Enlow T, Holmes GL, et al. Lamictal (lamotrigine) monotherapy for typical absence seizures in children. Epilepsia 1999; 40: 973–9

Mikati MA, Holmes GL. Lamotrigine in absence and primary generalized epilepsies. J Child Neurol 1997; 12Suppl. 1:S29–37

Yuen AW. Lamotrigine: a review of antiepileptic efficacy. Epilepsia 1994; 35Suppl. 5: S33–6

Beran RG, Berkovic SF, Dunagan FM, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of lamotrigine in treatment-resistant generalised epilepsy. Epilepsia 1998; 39: 1329–33

Besag FM, Wallace SJ, Dulac O, et al. Lamotrigine for the treatment of epilepsy in childhood. J Pediatr 1995; 127: 991–7

Panayiotopoulos CP. Beneficial effect of relatively small doses of lamotrigine. Epilepsia 1999; 40: 1171–2

Manonmani V, Wallace SJ. Epilepsy with myoclonic absences. Arch Dis Child 1994; 70: 288–90

Buchanan N. Lamotrigine: clinical experience in 200 patients with epilepsy with follow-up to four years. Seizure 1996; 5: 209–14

Brodie MJ, Yuen AW. Lamotrigine substitution study: evidence for synergism with sodium valproate? 105 Study Group. Epilepsy Res 1997; 26: 423–32

Reutens DC, Duncan JS, Patsalos PN. Disabling tremor after lamotrigine with sodium valproate. Lancet 1993; 342: 185–6

Echaniz-Laguna A, Thiriaux A, Ruolt-Olivesi I, et al. Lupus anticoagulant induced by the combination of valproate and lamotrigine. Epilepsia 1999; 40: 1661–3

Fayad M, Choueiri R, Mikati M. Potential hepatotoxicity of lamotrigine. Pediatr Neurol 2000; 22: 49–52

Frank LM. Lamictal: lamotrigine monotherapy for typical absence seizures in children. Epilepsia 2000; 41: 359–60

van Rijn CM, Weyn Banningh EW, Coenen AM. Effects of lamotrigine on absence seizures in rats. Pol J Pharmacol 1994; 46: 467–70

Brodie MJ, Overstall PW, Giorgi L. Multicentre, double-blind, randomised comparison between lamotrigine and carbamazepine in elderly patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy. The UK Lamotrigine Elderly Study Group. Epilepsy Res 1999; 37: 81–7

Gillham R, Kane K, Bryant-Comstock L, et al. A double-blind comparison of lamotrigine and carbamazepine in newly diagnosed epilepsy with health-related quality of life as an outcome measure. Seizure 2000; 9: 375–9

Steiner TJ, Dellaportas CI, Findley LJ, et al. Lamotrigine monotherapy in newly diagnosed untreated epilepsy: a double-blind comparison with phenytoin. Epilepsia 1999; 40: 601–7

Mullens EL. Lamotrigine monotherapy in epilepsy. Clin Drug Invest 1998; 16: 125–33

Guberman AH, Besag FM, Brodie MJ, et al. Lamotrigine-associated rash: risk/benefit considerations in adults and children. Epilepsia 1999; 40: 985–91

Fitton A, Goa KL. Lamotrigine: an update of its pharmacology and therapeutic use in epilepsy. Drugs 1995; 50: 691–713

Naito H, Wachi M, Nishida M. Clinical effects and plasma concentrations of long-term clonazepam monotherapy in previously untreated epileptics. Acta Neurol Scand 1987; 76: 58–63

Obeid T, Panayiotopoulos CP. Clonazepam in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsia 1989; 30: 603–6

Mikkelsen B, Birket-Smith E, Bradt S, et al. Clonazepam in the treatment of epilepsy: a controlled clinical trial in simple absences, bilateral massive epileptic myoclonus, and atonic seizures. Arch Neurol 1976; 33: 322–5

Browne TR. Clonazepam. N Engl J Med 1978; 299: 812–6

Nanda RN, Johnson RH, Keogh HJ, et al. Treatment of epilepsy with clonazepam and its effect on other anticonvulsants. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1977; 40: 538–43

Ames FR, Enderstein O. Clinical and EEG response to clonazepam in four patients with self-induced photosensitive epilepsy. S Afr Med J 1976; 50: 1432–4

Browne TR, Penry JK. Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy: a review. Epilepsia 1973; 14: 277–310

Martin D, Hirt HR. Clinical experience with clonazepam (rivotril) in the treatment of epilepsies in infancy and childhood. Neuropediatrics 1973; 4: 245–66

Lund M, Trolle E. Clonazepam in the treatment of epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand 1973; 49Suppl. 53: 82–90

Dreifuss FE, Penry JK, Rose SW, et al. Serum clonazepam concentrations in children with absence seizures. Neurology 1975; 25: 255–8

Sato S, Penry JK, Dreifuss FE. Clonazepam in the treatment of absence seizures: a double blind clinical trial [abstract]. Neurology 1977; 27: 371

Watson B. Absence status and the concurrent administration of clonazepam and valproate sodium [letter]. Am J Hosp Pharm 1979; 36: 887

Mireles R, Leppik IE. Valproate and clonazepam comedication in patients with intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia 1985; 26: 122–6

Sugai K. Seizures with clonazepam: discontinuation and suggestions for safe discontinuation rates in children. Epilepsia 1993; 34: 1089–97

Lombroso CT, Forsythe I. Long term follow-up of acetazolamide (diamox) in the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsia 1969; 1: 493–500

Chiao DH, Plumb RL. Diamox in epilepsy: a review of 178 cases. J Pediatr 1961; 58: 211–8

Resor Jnr SR, Resor LD. Chronic acetazolamide monotherapy in the treatment of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Neurology 1990; 40: 1677–81

Panayiotopoulos CP, Agathonikou A, Sharoqi IA, et al. Vigabatrin aggravates absences and absence status. Neurology 1997; 49: 1467

Montouris G, Biton V, Rosenfeld W, et al. Nonfocal generalized tonic-clonic seizures: response during long-term topiramate treatment. Epilepsia 2000; 41Suppl. 1: S77–81

Klitgaard H, Matagne A, Gobert J, et al. Evidence for a unique profile of levetiracetam in rodent models of seizures and epilepsy. Eur J Pharmacol 1998; 353: 191–206

Snead OC, Hosey LC. Exacerbation of seizures in children by carbamazepine. N Engl J Med 1985; 313: 916–21

Liporace JD, Sperling MR, Dichter MA. Absence seizures and carbamazepine in adults. Epilepsia 1994; 35: 1026–8

Schapel G, Chadwick D. Tiagabine and non-convulsive status epilepticus. Seizure 1996; 5: 153–6

Eckardt KM, Steinhoff BJ. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in two patients receiving tiagabine treatment. Epilepsia 1998; 39: 671–4

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge the significant suggestions and contributions of Dr P.N. Patsalos in the initial drafts of this report.

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest in relation to drugs or other matters in this report. In the last 7 years he has not participated in drug-sponsored studies and has not accepted invitations from drug companies to either speak at or attend meetings at their expense. In the early 1990s the author had limited paid presentations (≈20) for Wellcome, Marion Merrel Dow, Sanofi and Ciba-Geigy. Over the same period, Marion Merrel Dow had sponsored a clinical research fellow in the author’s department, Sanofi had sponsored an international meeting and Parke-Davis another international meeting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Panayiotopoulos, C.P. Treatment of Typical Absence Seizures and Related Epileptic Syndromes. Paediatr Drugs 3, 379–403 (2001). https://doi.org/10.2165/00128072-200103050-00006

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00128072-200103050-00006