Summary:

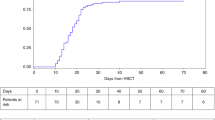

Our objective was to study the outcome of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for Shwachman-Diamond Syndrome (SDS). Among 71 SDS patients included in the French Severe Chronic Neutropenia Registry, 10 received HSCT between 1987 and 2004 in five institutions. The indications were bone marrow failure in five cases, and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or leukemia in five cases. The median follow-up of patients who survived without relapse is 6.9 years (3.1–16.8 years). The conditioning regimen consisted of a busulfan–cyclophosphamide combination (n=6) or total body irradiation plus chemotherapy (n=4). Six patients received stem cells from unrelated donors and four from identical siblings. Engraftment was complete in eight patients and unassessable in two patients. These latter two patients died of infections 32 and 36 days after HSCT, with grade IV graft-versus-host disease and multiorgan dysfunction. A third patient died from an acute respiratory distress syndrome 17 months after HSCT with progressive granulocytic sarcoma. One patient had an MDS relapse 4 months after HSCT and died 10 months later. The overall 5-year event-free survival rate is 60±15%. We conclude that HSCT is feasible for patients with SDS who develop bone marrow failure or malignant transformation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Shwachman-Diamond Syndrome (SDS) (OMIN260400) is a multisystem autosomal recessive disorder characterized by exocrine pancreatic dysfunction, bony metaphyseal dysostosis, mild intellectual retardation, and variable neutropenia.1 Almost all patients have a mutation in the SBDS gene located on chromosome 7.2 Bone marrow failure and myelodysplasia/acute leukemia are the main life-threatening complications. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is currently the only potentially curative treatment for these latter patients. Only 24 HSCT procedures have been described in this setting, in 18 separate publications.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Here we report the outcomes of 10 SDS patients included in the French Severe Chronic Neutropenia Registry who underwent HSCT during the last 15 years.

Patients and methods

Registry organization and disease definition

The French Severe Chronic Neutropenia Registry was created in 1994, with approval from the French computer watchdog commission (CNIL Certificate No 97075). The patients’ files are monitored by clinical research associates who visited each center at least once a year. All patients with SDS are included in the registry, even if they are not profoundly neutropenic. SDS was diagnosed on the basis of neutropenia associated with exocrine pancreatic deficiency and skeletal, skin or liver abnormalities, after Pearson's syndrome had been ruled out. The patients or next of kin were required to give their informed consent to participation to the registry. The French SCN database was crossed with the French transplant database (Etablissement Français des Greffes). A total of 71 patients were included in the SDS database, and a complete report of the survey, analyzed at the cut-off date of March 2003, has been published elsewhere.21 In all, 11 patients developed bone marrow failure, which was transient in five cases and persistent (>3 months) in six cases. Among these latter six patients, the patient who did not receive HSCT died. Eight patients developed MDS/leukemia, of whom three patients who were not transplanted died. SBDS gene mutations were evaluated as described elsewhere.2

Definition of hematological events

Acute leukemia was defined by WHO criteria, that is, at least 20% of blast cells on bone marrow smears. As dysplastic cytological abnormalities were nearly always present in these patients, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) was diagnosed if cytological abnormalities in addition to refractory anemia or thrombocytopenia requiring blood transfusion, as well as clonal cytogenetic abnormalities were present. Bone marrow failure was diagnosed in case of refractory anemia or thrombocytopenia requiring blood transfusion, if no cytogenetic clonal abnormalities were found. The time of bone marrow failure was recorded as the date of the first transfusion, and the time of MDS diagnosis was the date when the first cytogenetic abnormalities were detected.

Statistical methods

Stata® software version 8 was used for all statistical analyses. The end point for survival analyses was relapse (if MDS/acute leukemia (AL)) or death. The period taken into account was the interval between HSCT and either death or MDS/AL relapse or the last examination when no event occurred. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to construct survival rates. The cutoff date for this analysis was June 30, 2005. The median follow-up for the six disease-free surviving patients is 7.6 years (3.9–16.9 years).

Description of the patients prior to HSCT

The patient group consisted of six males and four females. Median age at transplantation was 11.2 years (1.1–27.7 years). Four patients were screened for SBDS mutations and all were positive.

Patients who had bone marrow failure tended to be younger than those who developed MDS/AL (median age 7.2 vs 16.5 year; P=0.07) and the interval between diagnosis of SDS and the hematological event was lower in bone marrow failure than in MDS/AL (median age 1.6 vs 13.5 year; P=0.02). The median interval between the hematological event and HSCT was 0.76 years, and was longer in patients with bone marrow failure than in those with MDS/AL (1.8 vs 0.3 year, P=0.009). Polychemotherapy with an AML-like regimen, including high-dose cytarabine, mitoxantrone, VP16 and amsacrine, was administered to one of the five patients with MDS/leukemia; it resulted in partial disease control and disappearance of the cytogenetic clone, but cytological bone marrow abnormalities persisted (about 5% blasts). The other four patients with MDS did not receive chemotherapy prior to HSCT. The clinical and hematological characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

HSCT characteristics

Four patients received marrow from a matched sibling transplant, while six patients received HSCT from unrelated donors (three 10/10 loci-matched unrelated donors and three single-antigen-mismatch donors). Bone marrow was used in all cases and was T cell-depleted in two cases.

All the patients received preparatory myeloablation. Six patients received a combination of busulfan (16 mg/kg in four cases and 13 mg/kg in one case) and cyclophosphamide (200 mg/kg), plus antithymocyte globulin in three cases. Four patients received total body irradiation (12 grays), combined with cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg) in three cases and with melphalan (180 mg/m2) in one case. The total number of infused nucleated cells ranged from 0.7 × 108–29.8 × 108/kg (median 4 × 108/kg).

Graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of methotrexate and cyclosporine A (CSA) in five cases, methotrexate, CSA and steroids in two cases, CSA alone in two cases and steroids alone in one case.

Engraftment

Chimerism analysis was performed by means of cytogenetics or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of microsatellites.

Results

Hematological recovery after HSCT and engraftment

Engraftment could not be evaluated in two cases because of early death, while full hematological recovery occurred in the other eight cases. The median time required for the neutrophil count to reach 0.5 × 109/l was 22 days (range 15–44 days). The platelet count reached 50 × 109/l after 19–155 days (median 29.5 days), without further transfusions. All the patients who are alive and disease-free are currently free of erythrocyte and platelet transfusions. Neutrophil counts normalized in every case.(Table 2)

Engraftment

Complete chimerism was found in all eight assessable patients.

Graft-versus-host disease

Three patients developed grade IV acute GVHD (skin/gut in two and skin/liver in one) after receiving a MUD transplant in two cases and a matched sibling transplant in one case. Two patients with grade IV GVHD died. Three patients had grade II GVHD. Two patients developed chronic GVHD, one case with a sicca syndrome and one case with chronic cutaneous GVHD, with persistent livedo.

Survival, causes of death and complications

Four patients died. The overall 5-year event-free survival rate was 60±15%. Two early deaths occurred. One patient (UPN 233015081) developed acute grade IV GVHD, thrombocytopenic microangiopathy with multiorgan failure and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia sepsis, and died on day 32 of Coronavirus 229E pneumonia.22 The second patient (UPN 233015253) died 37 days after HSCT from acute grade IV GVHD, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and HHV6 infection. The third patient (UPN 233015038) developed granulocytic sarcoma of the knee, ischium and shoulder, 1 year after HSCT. Monosomy 7 was detected in tumor cells by FISH analysis. The granulocytic sarcoma was treated with local radiotherapy. At the time of death (due to an undocumented acute respiratory distress syndrome), the marrow morphology was normal and no cytogenetic aberrations were detected. The disease course of this patient was remarkable. On day 40 after bone marrow transplantation (BMT), blast cells were observed on a blood smear, concomitantly with partial chimerism (28% of donor cells). A donor lymphocyte infusion was given on day 90, resulting in the disappearance of blast cells and in full donor chimerism. A fourth patient (UPN 233015117) with MDS/AL relapsed 4 months after transplantation, and died 10 months later from a hemorrhagic syndrome.

These four patients had received HSCT for MDS/AL. Although the number of patients is small, survival was significantly poorer in patients who received HSCT for malignancy than for bone marrow failure, four of the five deaths involving patients with MDS/AL and the other death involving a patient with BMF (log rank test, P=0.01).

One patient had long-term complications, with aseptic osteonecrosis, cardiac hypokinesia, chronic keratitis and amenorrhea. Despite the correction of hematological abnormalities, other clinical characteristics of SDS such as pancreatic insufficiency, short stature and impaired cognitive performance are still present in all survivors, albeit with no apparent modifications related to HSCT.

Discussion

We report the outcome of HSCT in 10 patients with SDS and severe hematological complications (bone marrow failure in five cases and myelodysplasia/AL in five cases). Bone marrow aplasia and myelodysplasia/AL appear to be the most serious complications of SDS, and are always fatal despite conventional management with transfusions and chemotherapy. In SDS, AL is diagnosed on the basis of cytologic criteria. It can, however, be difficult to distinguish between bone marrow aplasia and myelodysplasia on the sole basis of cytologic bone marrow studies. Indeed, cellular dysplasia is present in both instances and the cytologic aspects do not correspond to the FAB classification of myelodysplasias. It is therefore crucial to follow cytologic bone marrow studies by cytogenetic examination in order to distinguish between simple bone marrow depletion and clonal progression (‘myelodysplasia’). In addition, the presence of a cytogenetic anomaly of iso chromosome 7, or a deletion of chromosome 20, as found in one of our patients, has also been observed in patients without transfusion requirements and with nonfatal outcome,7, 23, 24 complicating the decision to proceed with HSCT.

As shown here, marrow transplantation with both sibling donors and matched unrelated donors can correct the stem cell disorder encountered in SDS. Full and sustained engraftment was observed in eight patients, arguing against a major stromal defect in SDS.25 Despite the small number of patients, we found a significant difference in event-free survival between patients receiving HSCT for bone marrow aplasia and those undergoing the procedure for leukemic transformation. Such a difference, albeit nonsignificant, was also observed among the 23 published cases of HSCT for SDS for which this information is mentioned (11 deaths or relapses among 17 patients with MDS/AL; and one death among six patients with bone marrow failure, P=0.07).3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

Several factors may explain the poor results of HSCT for myelodysplasia/AL in SDS. HSCT failed to correct the leukemia in one of our patients and in three of the 15 patients described in the literature. In addition, patients with SDS appear to be more susceptible to the toxicity of the HSCT procedure than are patients with other myelodysplastic disorders associated with monosomy 7, like the Kostmann syndrome26 and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.27 This susceptibility may be related to older age or to disease characteristics. Indeed, there is a marked age difference between patients receiving HSCT for bone marrow aplasia and for leukemic transformation, both in our series and in the literature (median age 4.5 and 13 years, respectively). Several risk factors could progress with age in this setting, including the nutritional consequences of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, liver disease, repeated infections and cardiac disorders. A risk of cardiomyopathy has been reported in patients with SDS in the absence of HSCT, fibrosis and necrotic lesions being found in 50% of SDS patients at necropsy; this was also the case of patient UPN 233015081, whose sibling died of cardiomyopathy. It is therefore necessary to carefully assess nutritional, cardiac and hepatic status prior to transplantation.

All the patients received a myeloablative-conditioning regimen prior to HSCT, usually consisting of the busulfan–cyclophosphamide combination. In patients with bone marrow aplasia, who are generally under 5 years of age, this conditioning appears effective and well tolerated. Stability of the engraftment over several years suggests that more intensive conditioning is not warranted. In contrast, the poor results in patients with leukemic transformation suggest that milder conditioning would be inappropriate and that very careful attention must be paid to nutritional status.

In conclusion, allogeneic HSCT can be envisaged for patients with SDS who become transfusion-dependent, with or without clonal cytogenetic features, and for those who develop overt leukemia. Our results indicate that BMT is associated with significant morbidity, potentially owing to pre-existing poor nutritional status, immune deficiency and/or the underlying disease. These patients should be closely monitored for infections after HSCT, and their nutritional status should be optimized before the procedure.

References

Dror Y, Freedman MH . Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Br J Haematol 2002; 118: 701–713.

Boocock GR, Morrison JA, Popovic M et al. Mutations in SBDS are associated with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Nat Genet 2003; 33: 97–101.

Arseniev L, Diedrich H, Link H . Allogeneic bone marrow transplatation in a patient with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Ann Hematol 1996; 72: 83–84.

Barrios N, Kirkpatrick D, Regueira O et al. Bone marrow transplant in Shwachman Diamond syndrome. Br J Haematol 1991; 79: 337–338.

Bunin N, Leahey A, Dunn S . Related donor liver transplant for veno-occlusive disease following T-depleted unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation 1996; 61: 664–666.

Cesaro S, Guariso G, Calore E et al. Successful unrelated bone marrow transplantation for Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant 2001; 27: 97–99.

Cunningham J, Sales M, Pearce A et al. Does isochromosome 7q mandate bone marrow transplant in children with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome? Br J Haematol 2002; 119: 1062–1069.

Davies SM, Wagner JE, DeFor T et al. Unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation for children and adolescents with aplastic anaemia or myelodysplasia. Br J Haematol 1997; 96: 749–756.

Dokal I, Rule S, Chen F et al. Adult onset of acute myeloid leukaemia (M6) in patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Br J Haematol 1997; 99: 171–173.

Faber J, Lauener R, Wick F et al. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: early bone marrow transplantation in a high risk patient and new clues to pathogenesis. Eur J Pediatr 1999; 158: 995–1000.

Fleitz J, Rumelhart S, Goldman F et al. Successful allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant 2002; 29: 75–79.

Hsu JW, Vogelsang G, Jones RJ, Brodsky RA . Bone marrow transplantation in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant 2002; 30: 255–258.

Miano M, Porta F, Locatelli F et al. Unrelated donor marrow transplantation for inborn errors. Bone Marrow Transplant 1998; 21 (Suppl 2): S37–S41.

Mitsui T, Kawakami T, Sendo D et al. Successful unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation for Shwachman-Diamond syndrome with leukemia. Int J Hematol 2004; 79: 189–192.

Okcu F, Roberts WM, Chan KW . Bone marrow transplantation in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: report of two cases and review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplant 1998; 21: 849–851.

Park SY, Chae MB, Kwack YG et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome with malignant myeloid transformation. A case report. Korean J Intern Med 2002; 17: 204–206.

Ritchie DS, Angus PW, Bhathal PS, Grigg AP . Liver failure complicating non-alcoholic steatohepatitis following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant 2002; 29: 931–933.

Seymour JF, Escudier SM . Acute leukemia complicating bone marrow hypoplasia in an adult with Shwachman's syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma 1993; 12: 131–135.

Smith OP, Chan MY, Evans J, Veys P . Shwachman-Diamond syndrome and matched unrelated donor BMT. Bone Marrow Transplant 1995; 16: 717–718.

Tsai PH, Sahdev I, Herry A, Lipton JM . Fatal cyclophosphamide-induced congestive heart failure in a 10-year-old boy with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome and severe bone marrow failure treated with allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1990; 12: 472–476.

Donadieu J, Leblanc T, Bader MB et al. Analysis of risk factors for myelodysplasias, leukemias and death from infection among patients with congenital neutropenia. Experience of the French Severe Chronic Neutropenia Study Group. Haematologica 2005; 90: 45–53.

Pene F, Merlat A, Vabret A et al. Coronavirus 229E-related pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37: 929–932.

Dror Y, Squire J, Durie P, Freedman MH . Malignant myeloid transformation with isochromosome 7q in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Leukemia 1998; 12: 1591–1595.

Dror Y, Durie P, Ginzberg H et al. Clonal evolution in marrows of patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: a prospective 5-year follow-up study. Exp Hematol 2002; 30: 659–669.

Dror Y, Freedman MH . Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: An inherited preleukemic bone marrow failure disorder with aberrant hematopoietic progenitors and faulty marrow microenvironment. Blood 1999; 94: 3048–3054.

Ferry C, Ouachee M, Leblanc T et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in severe congenital neutropenia: experience of the French SCN register. Bone Marrow Transplant 2005; 35: 45–50.

Donadieu J, Stephan JL, Blanche S et al. Treatment of juvenile chronic myelomonocytic leukemia by allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 1994; 13: 777–782.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grant RAF0007 from the Inserm AFM Network for Rare Diseases, Société d’Hématologie et Immunologie Pédiatrique, Amgen SA, and Chugai Aventis. We thank Florence Mesnil (Etablissement Français des Greffes) for her participation in patient screening and David Young for editorial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Donadieu, J., Michel, G., Merlin, E. et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: experience of the French neutropenia registry. Bone Marrow Transplant 36, 787–792 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1705141

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1705141

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

HSCT may lower leukemia risk in ELANE neutropenia: a before–after study from the French Severe Congenital Neutropenia Registry

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2020)

-

Long-term outcome after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Shwachman–Diamond syndrome: a retrospective analysis and a review of the literature by the Severe Aplastic Anemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (SAAWP-EBMT)

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2020)

-

First experience of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation treatment of Shwachman–Diamond syndrome using unaffected HLA–matched sibling donor produced through preimplantation HLA typing

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2017)

-

Recommendations on hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for inherited bone marrow failure syndromes

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2015)

-

Congenital neutropenia: diagnosis, molecular bases and patient management

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2011)